Parenting is the hardest job in the world. You never get time off – not even when you’re sleeping, not even when you are at work and your children are at school. You don’t get paid – not, at least, in any financial sense. There are times when you feel overworked, overwhelmed, and underappreciated, and every single little mistake you make can come back at you like a boomerang, days or weeks or even years later. Being a mom – or indeed, a dad – can drain your emotional and physical energy. You have to be in a million places at once, do a million things at a time, be teacher, nurse, therapist, judge, and mediator – sometimes simultaneously. The job comes with huge dollops of guilt: guilt for not having the time to play with your child while the stove is boiling over and the dog is barfing; guilt for locking yourself in the bathroom for five minutes of alone-time; guilt for actually buying something for yourself instead of spending the money on your child; guilt for rushing the homework supervision because the dinner is not made and the washing machine is jammed.

To be fair, the job of parenting has the best rewards ever: the enormous, gap-toothed smiles; the giant bear-hugs; the peals of childhood laughter; the I love you Mommy’s; the chance to look at your sleeping children at night and be filled with the most profound, incredible love.

It is hard though, and us parents should be allowed to acknowledge that without that feeling of ever-present guilt.

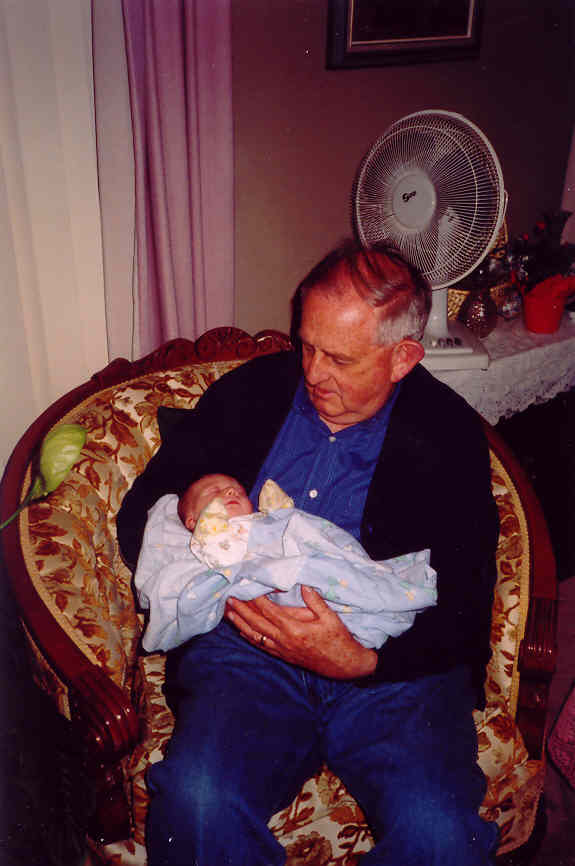

And yet, when I think of how tough it all is, I cannot help reflecting on what parenthood was like for my grandmother. She was born in 1903, and her third and final child – my mother – was born just a couple of years before the start of World War II. Despite being geographically remote from the events of the war, South Africa was part of the British Commonwealth, and therefore joined the Allied forces. My grandfather was one of the generation of men sent off into the front-lines of battle in North Africa.

This thrust my grandmother into the daunting and somewhat unexpected territory of single-parenting three young children in times of extreme economic hardship. Things weren’t so easy for women back then – if they wanted to work, they were teachers or nurses. The term “stay at home mom” had not even been invented because it was unspeakable that there would be any other kind of mom.

For me, as a mom raising children in 2011, I have a reasonable degree of control over my life. I can choose to work (actually, that’s a lie – I have to work if I want my kids to have shoes instead of walking barefoot in the snow). I have a wide choice of career options, I can express myself freely through my writing, and I can get out there and go running. I have the freedom – within the framework of my family life – to make my own choices and steer my life in a certain direction.

My grandmother did not have the same leeway. She was controlled in a big way by the events going on in the world at the time. She was, in many respects, a bystander in her own life. She could only watch and wait as the world went through its turmoil, and she had to raise her kids knowing that things could change at any moment, things that she had no control over. A telegram could arrive telling her that my grandfather had been killed. Supplies of something-or-other could abruptly run out, leaving her scrambling for an alternative. The war could end and my grandfather could come home. The war could continue and she might not see him for a very long time. He could come home minus a limb or suffering from severe psychological trauma. She had no way of knowing what was going to happen.

It was a day-to-day kind of existence for that generation of mothers. My grandmother, and other women in her position, did not have the luxury of making choices or setting goals for the future.

Yes, parenting is the hardest job in the world. But I think, in many ways, that it is not as hard as it used to be.

This week’s Indie Ink Challenge came from Tara Roberts, who gave me this prompt: She was a bystander in her own life.

I challenged The Drama Mama with the prompt: Tell a story about how missing a bus for a few seconds can change your life.