Last night, my son George was upset. He was distressed for the entire evening, crying and looking at us sadly with tears escaping from his beautiful big blue eyes. I could tell that this wasn’t just a case of a kid being in a bad mood. Something specific was bugging him. I just didn’t know what it was.

Last night, my son George was upset. He was distressed for the entire evening, crying and looking at us sadly with tears escaping from his beautiful big blue eyes. I could tell that this wasn’t just a case of a kid being in a bad mood. Something specific was bugging him. I just didn’t know what it was.

It was heartbreaking. There was this child, my beautiful boy, clearly wanting or needing something, and he was not able to communicate what it was. It was not for lack of trying. He was making supreme efforts to find the words and get them out, but no matter how much I tried, I just couldn’t understand.

In the end, George was just looking at me with an expression that told me he didn’t blame me for not getting it, that although he was sad, he was used to not being able to express himself, used to not being understood.

It was that look, the expression of resignation, that broke my heart. The idea that my child is already, at the age of 7, getting used to a life of hardship, just kills me. I guess this kind of acceptance has to happen sometime, because George’s life is never going to be the same as most other people’s, but still. It’s a difficult pill for a parent to swallow.

Moments like this strengthen my resolve where my running is concerned. On Sunday evening, I ran 14km on the treadmill. That’s a long way to run on a lab-rat machine, but really, I didn’t have any choice. Circumstances were such that it was the treadmill or nothing. And because I have a half-marathon a month from, now, I had to put in the distance.

Just because I deemed it necessary to run for 90 minutes on the treadmill, that doesn’t mean I liked it. It was very hard. The running part was OK. It was the mental resolve part that got me. Treadmill running is mind-numbingly dull, no matter what you do to try and distract yourself, and it took all of my self-discipline to keep going for the full distance.

Many of my long runs – even the ones I do on the open road – are tests more of my mental fortitude than my physical abilities. I know that I can run the distance. I have the base of physical fitness, and I have developed a running form that works for me. The mechanics of my body work just fine. The trouble is that my mind keeps trying to tell me that I’ve been running for a long time, and really, I should be getting tired by now. I have developed techniques to keep myself mentally strong during my runs. Playing music, thinking of things that are not running related, focusing on my body and how it feels as I run. The most effective technique I have, though, is this: all I have to do to keep going is think of the reason I’m doing it.

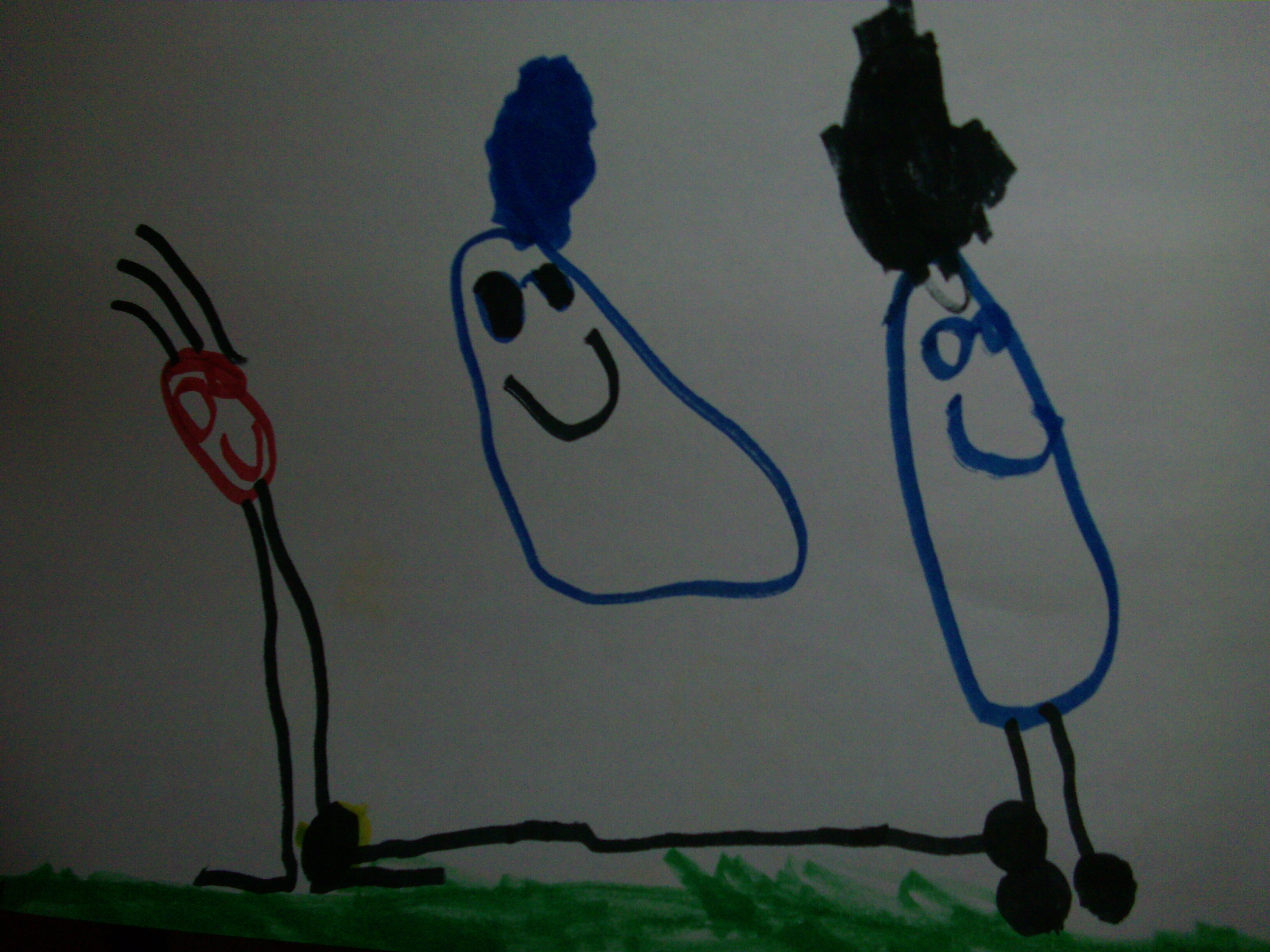

Every step I take, every aching muscle I endure, every toenail that I lose – it’s all for George. All of this training takes me closer to my Run For Autism, the event I use to raise funds for autism services to benefit my son and other people like him. Running for my child – what better motivation could there possibly be?

People sometimes ask me how I do it, how I go for all of those long runs and then, at the end of it, go out and race for thirteen miles.

For me, it’s easy. All I do is think of my boy. If he can live every day of his life with the challenges he faces, surely I can manage a two-hour run.

If he can do it, so can I. And he is my inspiration.

For details about my Run For Autism and how to support the cause, please visit my race page.