Since my son George was diagnosed with autism five years ago, I have learned – to some extent, at least – how to field the rude comments of strangers and the blatant stares of their children. Through my writing and through daily interactions, I do what I can to educate and inform, to discourage people from discriminating against my child on the grounds that he is “different”. I strive for awareness and acceptance, and I work towards a world in which everyone accepts George for the wonderful, albeit a bit quirky, person that he is.

In this quest I am part of a not-so-secret society of autism parents who have a common goal. We post and share autism awareness messages on our Facebook walls. We circulate articles about what to say and what not to say to an autism parent, and we brainstorm ways to make things easier for our children. In all of this, our message to the world is this: Accept our children, include them to the extent to which they are capable, and discover what wonderful people they are.

As passionate as I am about this cause, I do believe that if we’re not careful, we can take it too far. We can make the mistake of expecting the world to bend to our children no matter what, without making any effort to equip our children to live in the world.

During my afternoon commute from work, I regularly encounter a blind woman who has a service dog. When we get off the subway, we go to the same bus bay, although she doesn’t take the same bus as me. She waits patiently for her bus, politely asking people to let her know when her bus has arrived. She is so nice and charming, and people practically climb out of their own skins in their eagerness to assist her.

In contrast, there is a man during my morning commute on the subway who is confined to a wheelchair. He is rude and aggressive. He seems to be completely OK with literally pushing people out of the way in his efforts to be first onto the train when it arrives, and he acts as if he can behave as badly as he likes because he is disabled. People are not that inclined to help him and feed his sense of entitlement.

When George has meltdowns in public, there is often very little I can do about it, but that doesn’t stop me from trying. As I try to engage strategies to help him, I offer explanations of autism to anyone who might be nearby. Am I obligated to explain my son’s behaviour? Maybe not. But I do recognize that my son’s behaviour at those times can be disruptive and a little frightening to the people around us who cannot be expected to magically know that he has a invisible disability.

In the vast majority of cases, my explanations are met with smiles and nods of understanding. On the odd occasion, I have even received offers of help. Yes, there are always the people who tell me that I shouldn’t have my child out in public if he cannot control himself, or that my bad parenting is to blame, but there’s very little one can do about people with that kind of attitude.

The point is that the road to acceptance is a two-way street, with some effort required from both sides. It shouldn’t be all up to other people, who in many cases may not know how they’re supposed to act around someone with autism. The individual with autism (depending on the level of functioning) and his or her family should do their part to make things easier too.

When I was on the subway to work one morning, a girl of eleven or twelve boarded the train with her parents. With the sense that autism parents develop as an instinct, I knew that this girl had autism. She clearly had communication deficits, but she appeared to have a reasonable level of functioning in other ways. Since this was during the morning commute, there was standing room only on the train.

The girl lost it. Over and over, with increasing intensity, she screamed, “I want to sit down.”

Bear in mind that although I knew the girl had autism, in all likelihood the other passengers didn’t. Why would they? Autism is not a visible disability. To most of the people on the train, that girl was simply a brat acting out. Her parents did not offer any explanations, nor did they make any effort to stop the screaming or help their daughter.

As the screaming escalated to an ear-splitting “I! WANT! TO! SIT! DOWN!” a woman close to where I was standing gave up her seat to the girl, who instantly calmed down. No-one thanked the woman who had given up her seat: not the girl, and not her parents. The woman, quite justifiably, was annoyed. She said something to the girl’s mother about manners, and the girl’s mother made some obscure comeback about a commuter’s responsibility to give up their seat to people with disabilities. The woman shook her head in bafflement and moved towards the opposite end of the carriage.

I didn’t mind that the girl had started melting down over the lack of seats. People with autism do not have control over what triggers them.

However, I do mind that her parents expected everyone else to accommodate her without offering an explanation, and I mind even more that they allowed the situation to escalate without trying to help her. I believe that in their lack of action, they did a great disservice to the autism community.

The next time any of those commuters encounters a child having a meltdown in a public place, how understanding are they likely to be? Does this kind of thing not reinforce all of the negative stereotypes about autism that we are trying so hard to beat?

We (autism parents) spend a lot of time talking about how we wish people would accept our kids. But we cannot really expect someone to accept something when they don’t even realize there’s something to accept.

Is it acceptable for people to be rude and discriminatory towards individuals with autism? Absolutely not. That doesn’t mean, however, that everyone has an automatic obligation to cater to us and our children, no matter what, without a little bit of effort from our side.

We have to meet the world halfway on this one. Working with society, not against it, is ultimately what will build awareness, acceptance and inclusion.

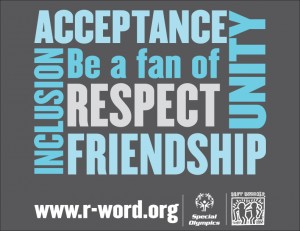

(Photo credit: Kirsten Doyle)