When I first started running in the winter of 1996, my dad was my first-ever coach. At that stage of my life, I was quitting smoking and giving up a host of very unhealthy lifestyle habits. My idea of running involved jogging for about thirty seconds and then walking for five minutes while trying to get my breath back. I was that out of shape. When Dad offered to coach me, I initially felt a little awkward. I mean, he was an ex-marathoner of note and he’d be coaching someone who could barely get off the couch. But he insisted that I since I had the spirit of a runner, the rest would follow easily enough.

Over the next few years, Dad gave me a ton of advice that came not from reading books, but from experience. He taught me about hydrating in small frequent sips rather than the occasional big gulp. He took me to the running store not for shoe shopping, but to make sure I knew how to pick out the right socks – something he said many runners fail to see the importance of. He told me that it was important to keep moving after a run instead of just stopping, and he showed me how matching my breathing to my pace would help me not only physically, but mentally as well.

While I was still living in Johannesburg, Dad and I spent many hours sitting on his patio drinking wine and chatting about the South African running scene. He would tell me why this guy was probably going to win the nationals despite being a rookie, and why that guy would crash and burn despite years of experience. He was usually right in his predictions.

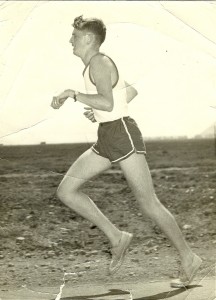

Now, seven years after his death, I have realized something that makes me very sad: I did not talk to him enough about his own days as a runner. Today I was looking through a scrapbook I have put together of newspaper clippings, certificates and photographs. I looked at the medals and trophies he won that I got when he died, and I read his training log. And I got a true appreciation for just how great a runner he was.

In his prime, Dad was one of South Africa’s elite marathon runners, featuring in the top ten lists for various distances. As a 22-year-old running his second marathon, he won a place on the podium by crossing the finish line in third place. He ran the now-defunct Peter Korkie ultramarathon – a distance of 37 miles or 59 kilometres – in a time of just over four hours. He ran sub three-hour marathons as a matter of course.

And I wish that I had asked him about those days. How old was he when he started running? What got him into it? What was it like, being a runner in those days?

Apart from a few anecdotes he shared about his days as a runner, and the artifacts that I have now in my possession, I know shamefully little about my dad’s journey as one of South Africa’s true running talents.

It’s not too late to try and find out, though. I have plans to go back to his roots, to the sports club he ran for, to try and find someone who ran with him.

Maybe he will guide me in my quest to find out more, just as I feel him guide me in the races I run today.

(Photo credit: unknown photographer – picture is from my dad’s running archives)