There are few things more surreal than waking up on the morning of your biggest race of the season – the event that you have spent all year preparing your body and mind for. You know that this is it. This is what everything you have done this season has been leading up to – every race, every long run in the pouring rain or blistering sun, every gruelling session of slogging repeatedly up the same hill.

As I got ready for the Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Half-Marathon on Sunday morning, I alternated between eerie calmness and frenetic nervousness. On the one hand, I felt ready. I had trained hard, and there was no question that my body would be able to handle the half-marathon – a distance that I had already run seven times in the last four years. On the other hand, I had just been through several months of the most mind-bending stress. My body was ready, but was my mind strong enough?

And would I be able to run 21.1km wearing a cape and a funny hat?

For the first time ever, I had decided to run a race in costume. This involved an autism-oriented logo…

… a hat spouting weird hair…

… and a cape.

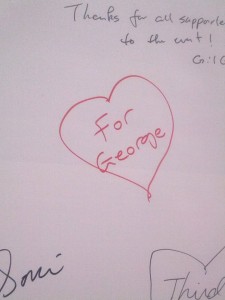

The day before the race, I wavered on the whole costume idea. I was going to feel very self-conscious at the start, walking around among thousands of people with blue hair spouting from my hat. But then I remembered what I had written on the message wall at the runner’s expo – the reason I was doing all of this.

As it turned out, I didn’t feel self-conscious at all. In the start area I saw several people wearing costumes. Besides, I was hanging out with Charlie, who like me was running for the the Geneva Centre for Autism. I was having too much fun to feel self-conscious.

When Charlie and I made our way to the start line, we found ourselves further back in the pack than we had intended, and we felt as if we waited forever before we finally started to shuffle forward. I wished Charlie luck, stepped across the timing mats, and the race was on.

Right from the start, I felt marvelous. The costume didn’t bother me in the slightest, and I didn’t have any of the awkward stiffness that I sometimes feel during the first couple of kilometres. For a change I didn’t start out too fast. I ran the first 7K at a nice easy pace – fast enough to keep up a respectable average speed, but not so fast that I would run out of steam before hitting the halfway mark. About a third of the way into the race I kicked it up a notch, and by the time I ran over the 10K timing mats I was cruising along very comfortably.

Three kilometres later, I reached the turnaround point, and I was feeling great. I was starting to tire and I still had eight kilometres to go, but I was now physically heading towards the finish line. I contemplated increasing my speed, but decided not to. I tend to struggle in the 18th and 19th kilometres of a half-marathon, and I wanted to make sure I would have the energy to get through that patch.

As I was running up the only real hill on the course, my fuel belt came off, and I had to stop to pick it up and secure it around my waist again. I was worried: my pacing had been so perfect, and this was just the kind of thing that could break the rhythm. But fortunately, I was able to get right back into it without losing more than a few seconds. I made up the time by sprinting for sixty or seventy metres, and then settled back into my regular pace.

As soon as I started the 18th kilometre, I hit my customary struggle. My legs started to feel like jelly and my brain started to tell me that I couldn’t do this anymore. Telling myself that this was only in my head, I ran on. I allowed myself to slow down a little, but I kept going. I got through that kilometre and the next one by counting in my head – a neat little trick I figured out that distracts my mind from what I’m actually doing.

All of a sudden, I saw what I had been waiting for – the marker indicating that I was now in the 20th kilometre. Just like that, my mind cleared and my jelly-like legs started to feel strong. I had just over two kilometres to go – less than 13 minutes of running. I could do this. I told my legs to go faster and they willingly obeyed. With one kilometre to go, I slowed down briefly to remove my ear buds. I didn’t need music now. There were crowds of spectators lining both sides of the road – they would carry me to the finish.

500 metres to go. About ninety seconds from now the finish line would be in my sights. Spectators were cheering for me by name and I was smiling and waving cheerfully, loving every moment. With 300 metres to go, I put every ounce of remaining energy into my legs and a mental picture of George, my son and inspiration, into my head.

I crossed the finish line with a time of 2:16:42 – a new personal best time. My legs were hurting, but my spirits were absolutely flying.

When I got home, I gave my finisher’s medal to the person I was doing all of this for. The smile on his face mirrored the feelings in my soul.

This year’s race is done, and I am already looking forward to next year’s event.