This is the first in a series of stories in response to the Ontario government’s announcement that IBI services are no longer available to children aged five and older. This disgraceful, discriminatory policy ignores the fact that autism doesn’t end at five. If you have a story that you would like told, send an email to kirsten(at)runningforautism(dot)com.

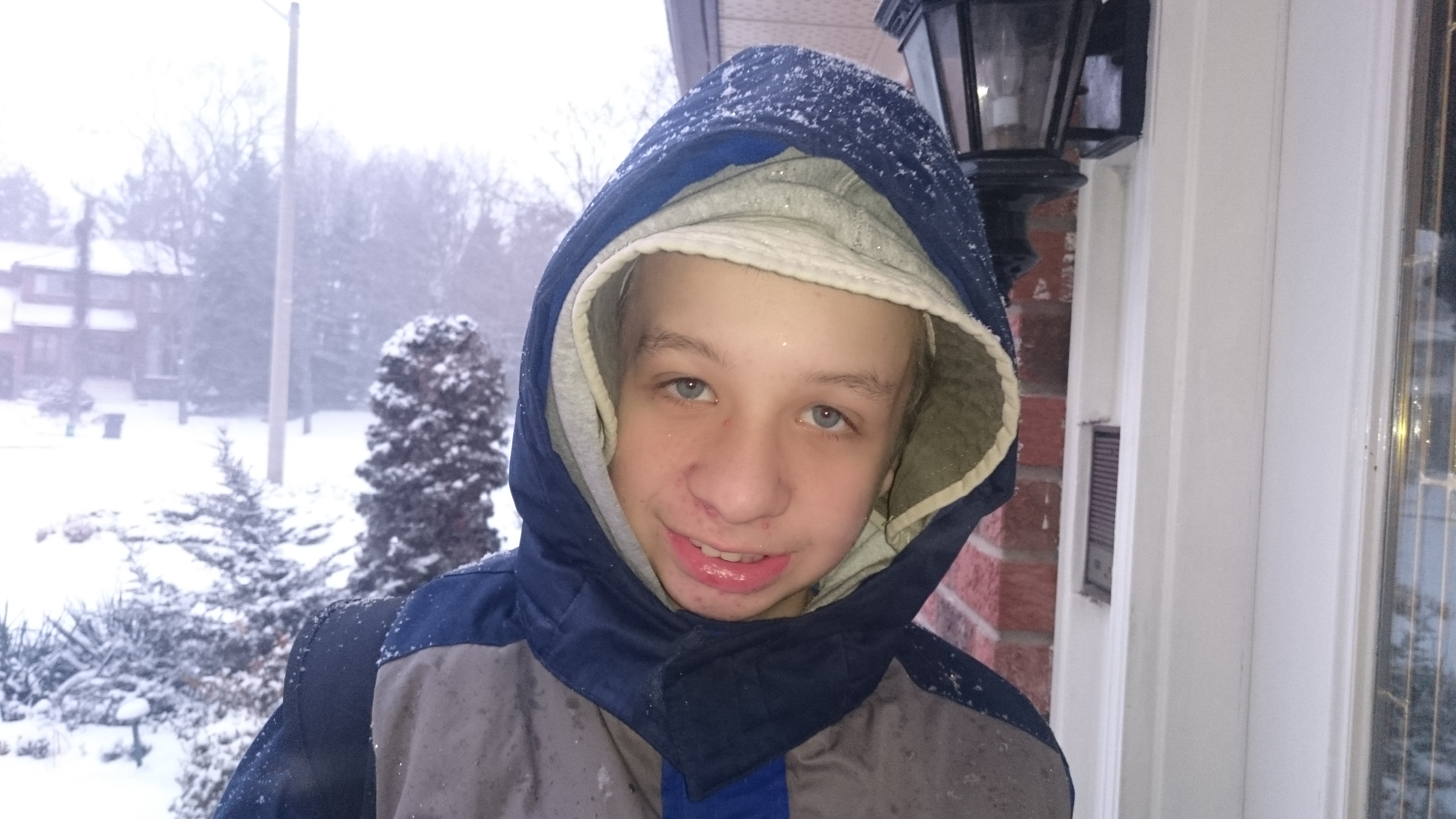

My son George was diagnosed with autism when he was almost four, a full year later than he should have been (the doctor’s initial refusal to refer him for an assessment is another story for another day). By the time he had gone through the government assessment and been deemed eligible for services (yet another story for yet another day), and served his time on the waitlist, he was a couple of months past his fifth birthday.

You know, that magical cut-off beyond which, according to the Ontario government, kids can no longer benefit from IBI therapy.

When George entered IBI at five years and three months, he functioned at an eleven-month level on verbal abilities, and at sixteen months on non-verbal abilities. His overall level of functioning was fourteen months.

He had a follow-up assessment at the age of six years and five months, a little over a year after starting IBI. The results were staggering. On verbal abilities, he was now functioning at 35 months, and on non-verbal abilities he was functioning at 51 months. Overall, he was at a level of 39 months.

Can we do the math here? My son gained almost two years in verbal skills and almost three years in non-verbal skills. Overall, he made gains of 25 months in a fourteen-month period.

These gains translated into an explosion of progress that was visible to everyone. George started to learn simple skills like getting dressed and using the washroom without assistance. He spelled out full, grammatically correct sentences using alphabetic fridge magnets, and for the first time, he was making his requests verbally. When he was six, he made his first deliberate joke, and we started to see his funny, quirky sense of humour.

There are no words to describe how grateful I am that George was born at the time he was, that he turned five in 2008 and not 2015 or 2016. Because in the new reality created by the Ontario government, he would have missed out on that rocket-like trajectory of progress. He would not be where he is today – a happy twelve-year-old who, while still clearly autistic, shows incredible amounts of potential.

I feel a sense of survivor’s remorse. I feel devastated for all of the parents who will not get the experiences with their kids that I had with George. My heart breaks when I think of the potential that is being flushed away, the kids who are being left behind, the parents whose hopes have been shattered.

IBI can and does benefit children of all ages. Nobody should be left behind because of an arbitrary age cut-off, because autism doesn’t end at five.

By Kirsten Doyle. Photo credit to the author.