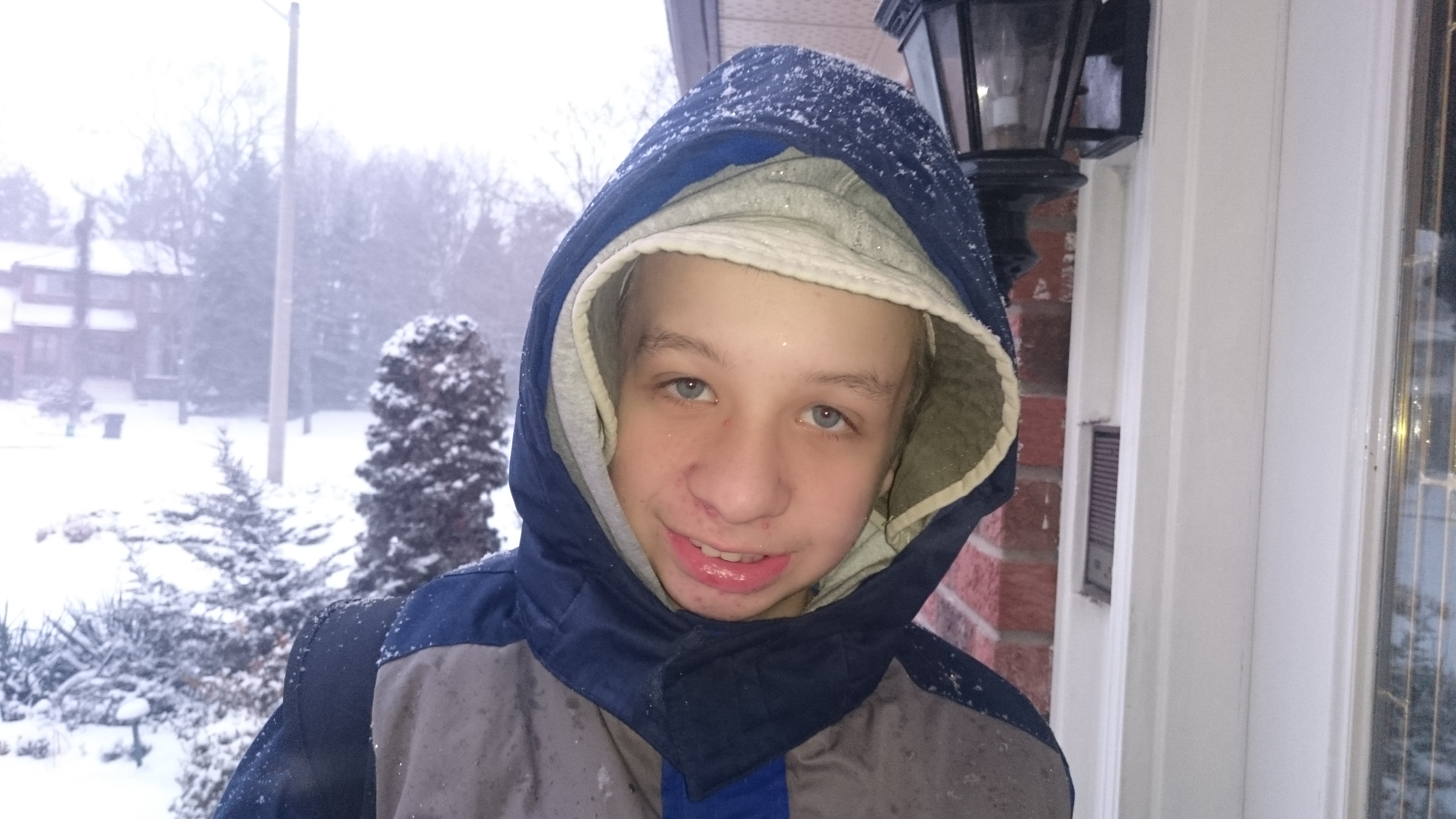

Our “Autism Doesn’t End At Five” series continues today, with the story of Jolie-Anne. In spite of steady success with IBI, Jolie-Anne is no longer eligible to receive services, simply because of an arbitrary age cut-off imposed by the Ontario government. If you have a story that you would like told, send an email to kirsten(at)runningforautism(dot)com.

When Jolie-Anne was just twenty months old, her mother suspected that she might have autism. After spending eighteen months on a waitlist for a developmental assessment, she was formally diagnosed when she was a little over three years old.

For the next three years, Jolie-Anne was on the waitlist for provincially funded IBI services. During this time, her mother dug deep into her bank account to pay for whatever early intervention she could afford – speech therapy, occupational therapy and ABA social groups.

Jolie-Anne’s fifth birthday came and went, and she was still on the IBI waitlist. Her parents were no longer prepared to wait – they decided that until the government came through, they would find a way to foot the massive bill for IBI themselves. They felt that they had little choice: in the months leading up to this decision, Jolie-Anne had made virtually no progress in spite of being in a special needs classroom with a full-time EA.

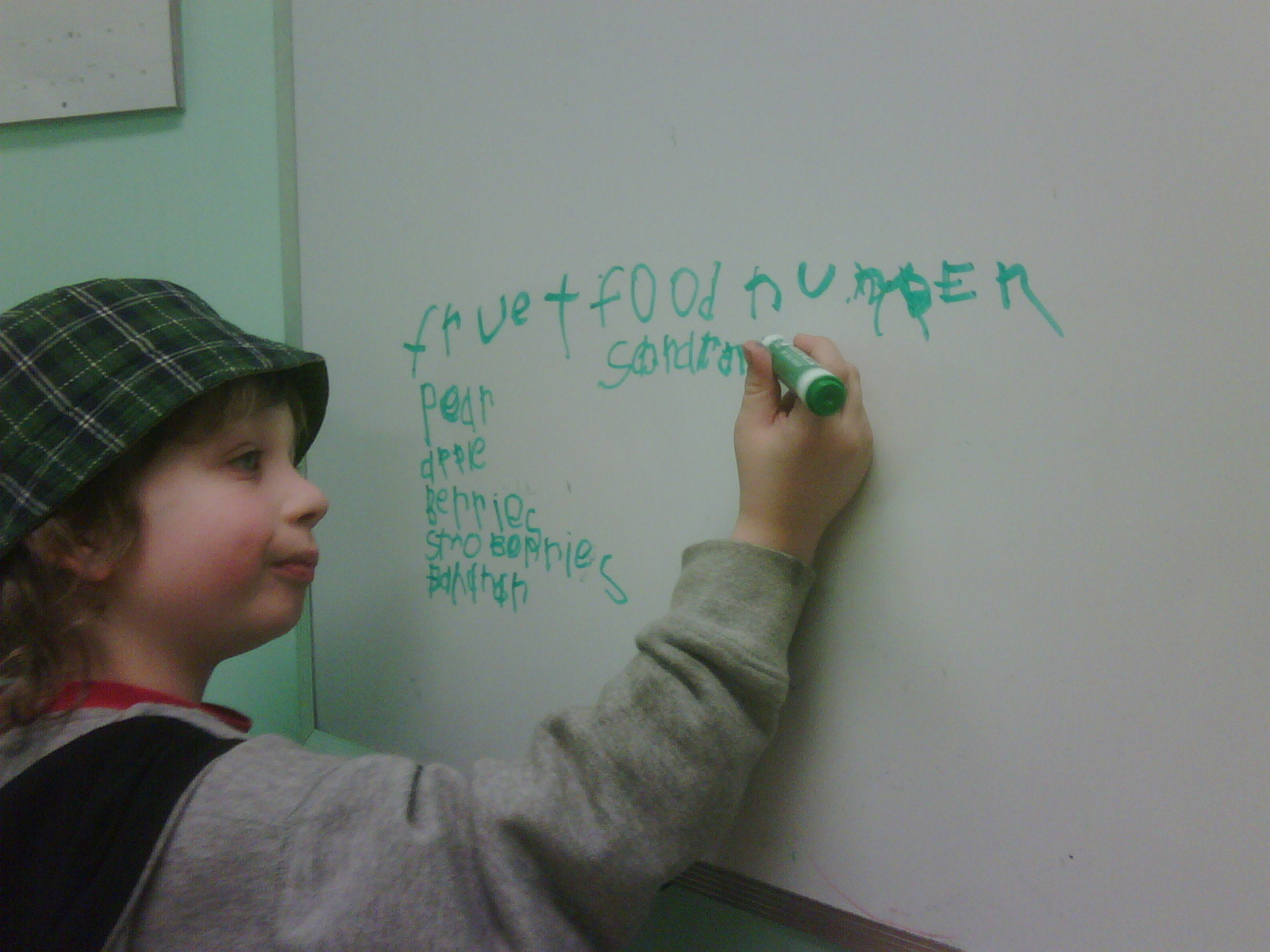

Almost immediately, Jolie-Anne’s family and IBI providers started to see a difference. For the first time, she had a voice. She started using words, making eye contact and forming friendships. She learned how to state her name, age and address. She acknowledged her grandfather for the first time and gave him a hug.

The progress came at a tremendous financial cost to the family. Jolie-Anne’s parents were overjoyed and relieved when they were finally granted government funding for IBI services in September last year. Jolie-Anne continued to acquire new skills and meet the therapy goals that were laid out for her.

Sadly, thanks to the Ontario government’s new policy to deny IBI services to children aged five and above, Jolie-Anne will not be able to continue with IBI therapy unless her family is able to stretch themselves financially, even more than they already have.

Jolie-Anne’s mom is thinking not only of her own daughter, but of other children who are impacted by this new policy.

“I think of all the kids, who like my daughter could start IBI at age five or later and benefit from the same life-changing results, but they will not have that opportunity. I am heartbroken.” – Tia, Jolie-Anne’s mom

It is more than a little disturbing that any government can decide that children are no longer deserving of life-changing therapy simply because they have reached a certain age. It is cruel to give the families of children with autism hope only to snatch it away. It is short-sighted to deny a child services that would enable him or her to ultimately get a job and contribute to the economy.

By Kirsten Doyle. Photo courtesy of Tia, Jolie-Anne’s mom.